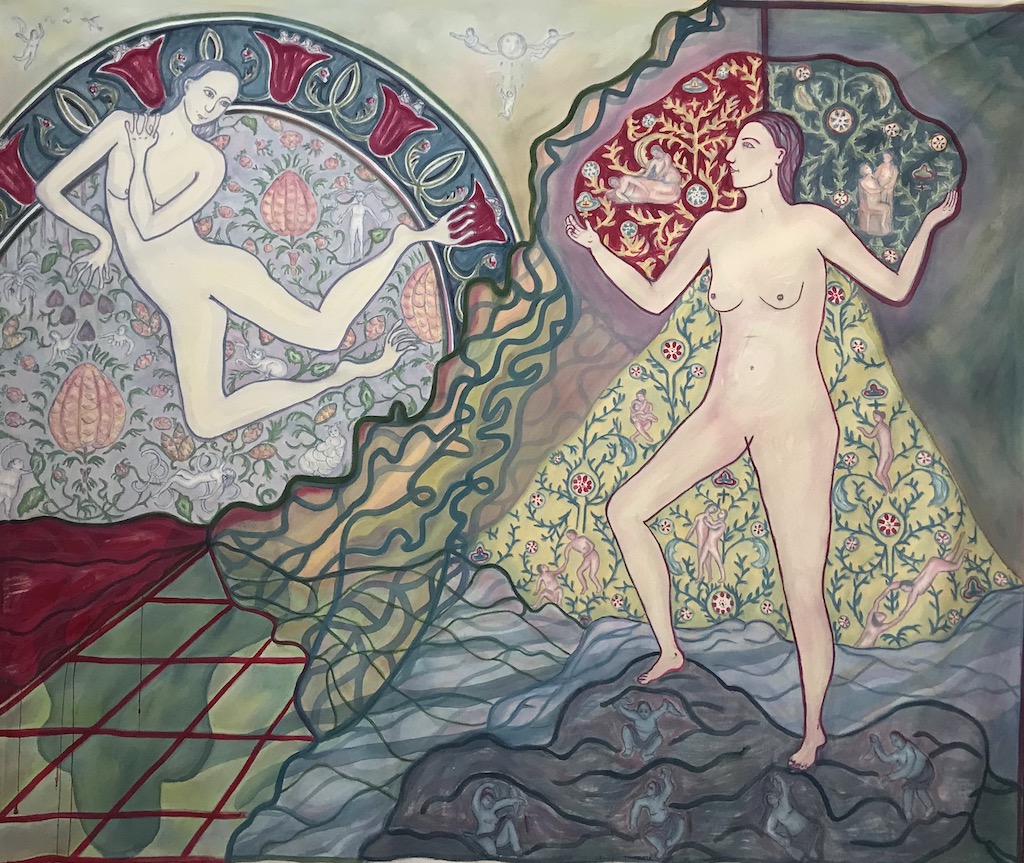

Figuras de convite (say welcome to yourself), acrylic on canvas, 160x160cm, 202

Delineating a different vision that re-centres and revives our perspective on familiar motifs and myths Figuras de convite was painted in a barn studio whilst on a self-directed residency in Boliquieme, Portugal. I set up the residency to explore and process new work inspired by place, rocks, landscapes, women and stories that make connections with Cornwall.

I was delighted to continue my obsession with the rocks and stones, the porous mezozoic limestone rocks that in contrast to Cornish granite are soft and permeable. I love the potential anthropomorphic metaphor for women who are often more ‘permeable’; open and empathetic to their surroundings and others, often at the cost of a sense of Self. Holed hagstones here are easily found, portholes to magical imaginings and pareidolic visiosn create figures, forms and metamorphosing cryptids from these incredible rocks. Local tales tell of the Stone girl of Salir, a common and universal myth of women turned to stone. I wondered what other tales might emerge from being in this place, a beautiful hinterland of hills, rocks and trees.

Beautiful fruiting trees besides orange and pomegranate – carob, walnut, olive, almond – and cork. Cork trees grow in special managed habitats called montados. They love poor dry rocky locations. And ancient techniques and skills passed down generations enable the harvesting of the outer bark of these magnificent tress without causing harm to the tree itself. The cork is left to dry and age for several months, allowing it to develop its unique characteristics of a beautiful honeycomb-like structure that is firm yet flexible.

The first figure I painted emerges from the cork trees. According to the Greeks every tree had a tree nymph or dryad and there were specific names for each type of tree nymph. Daphnaie were nymphs of the laurel trees. Maliades or Epimelides the nymphs of apple and other fruit trees. I have found myself wondering if there is a specific Greek appellation for cork tree nymphs. The relationship of humans to cork trees is potentially an example of symbiosis with nature and the material qualities as metaphor again for porosity and permeability – and flexibility.

The second main figure of the painting is inspired by the famous Portuguese art of tiles. The word Aluzejos come from ‘little stone’ (Arabic), and these tiles mimic porcelain white ground usually with cobalt oxide double firing. Dating back to 16th century these tile ‘paintings’ evoke the painting styles and decorative motifs of each age, and in the 18th century there was a fashion for life-size tile paintings of people to be displayed on the outside of buildings. These were called ‘Figuras de convite’, welcoming figures to greet guests. As I worked Ion the painting the title took on a personal meaning for me. I was thinking about the wonderful welcome I experienced in Boliquieme and giving myself permission to enjoy my hosts generosity. I began thinking of my own interpretation of ‘welcoming figures’ as ‘Say welcome to yourself’; a kind of gift to ourselves. Giving ourselves permission is a kind of self care, and welcoming different aspects of yourself/selves is an essential part of self-knowledge and self-acceptance.

Portuguese polychrome tile panels of aluzejos historically feature allegorical and mythological scenes that are often elaborately framed with friezes and borders but here the colourful border of the painting was based on patterns from Portuguese traditional folk dress. And of course there are many other references thrown in: carnations, the colour of pomegranates (which I picked and deseeded whilst there), and blue skies full of famous and mythical Portuguese creatures; the silver fox, (Zorra Borracdeura), the serpent (Coimbra), the Iberian wolf, the rooster (Galo de Barcelos), the ghost bear (Bicho Cirao) and the red kite.

All of these things are part of a rich cultural tapestry and the living texture of place. Fearful initially of using the somewhat stereotypical symbolism of the visitor, the outsider, I stopped worrying and embraced all as a starting point for future conversations with this beautiful place, where I was inspired by everything –even the thunderstorms and poorly chicken!

I was very grateful to my generous hosts and the conversations we had about the possible interpretations of the painting and the relationship between the two main figures. My love affair with this place and I look forward to spending more time here in future and discovering all its treasures.

November, 2024

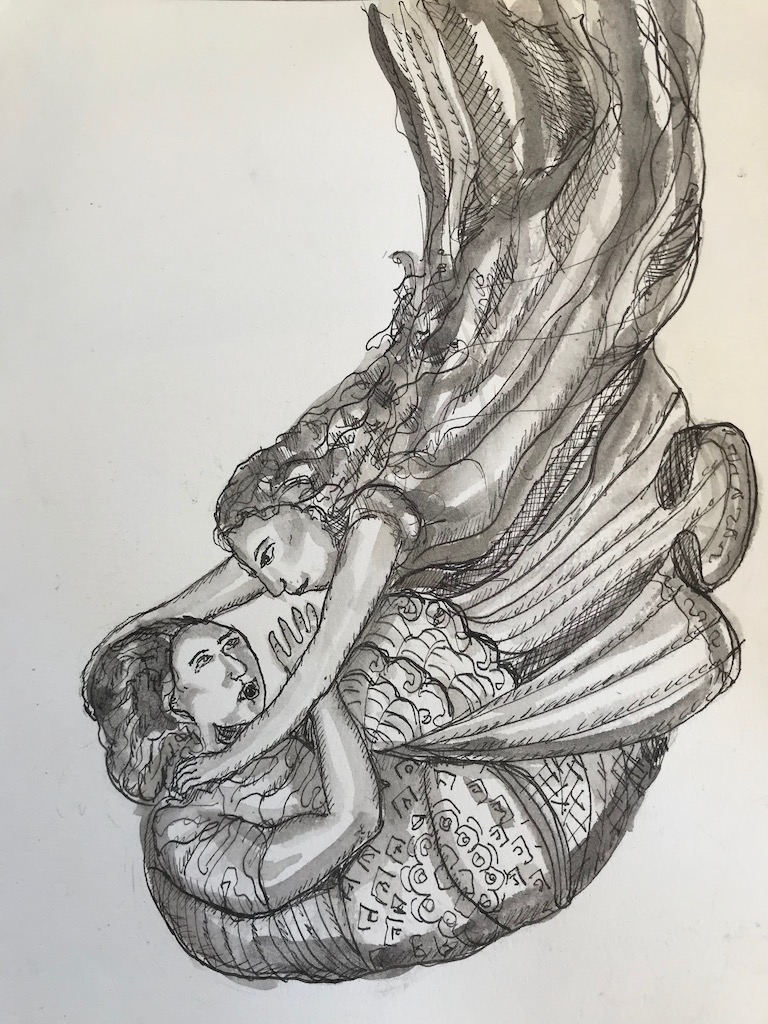

About Another glad day

I always resist referencing specific people, the figures in this painting are created as avatars, not stereotypes, These two main figures, one hybrid with distorted froglike fingers and toes, the other is standing on a rock a little like a Caspar David Friedrich rucken figure from the front, she is not however signalling that she has conquered or owns the landscape, as she also nods to William Blake’s Glad Day 1794-6 (often called ‘Albion Rose’).

Both figures are naked, communicating connectedness and vulnerability and power. They are ‘in the grip of convention and rationality the figure is stripped of clothing and has cast off the material world to welcome a new dawn ‘(Blake). Well a slightly sardonic ‘new dawn’: switching the gender of these powerful symbols doesn’t change a patriarchal world in which both nature and women are owned, controlled, and shaped to greedy needs, yet exposing devious cultural appropriations of both is a start.

New paintings explore fictions and polyphonic stories, exploring and interrogating local terrain, aiming to show how reflexive processes of embodiment create new stories that turn history and hierarchies inside out. Landscape and nature is expressive of specific cultural meanings and here in Cornwall local places are indicative of a myth of wildness and marketed as such. Yet natural phenomenon and places can stand for many things. The landscape and rock references in this painting are specifically from Treen, near the now famous Minack Theatre, built on the myth of a woman who with her bare hands created theatre on the edge of cliff. Her story amplified, appropriated, owned and sold on to others. The theatre-landscape of Treen is no longer be truly ‘wild’, if it ever was, so lets tell different stories about it.

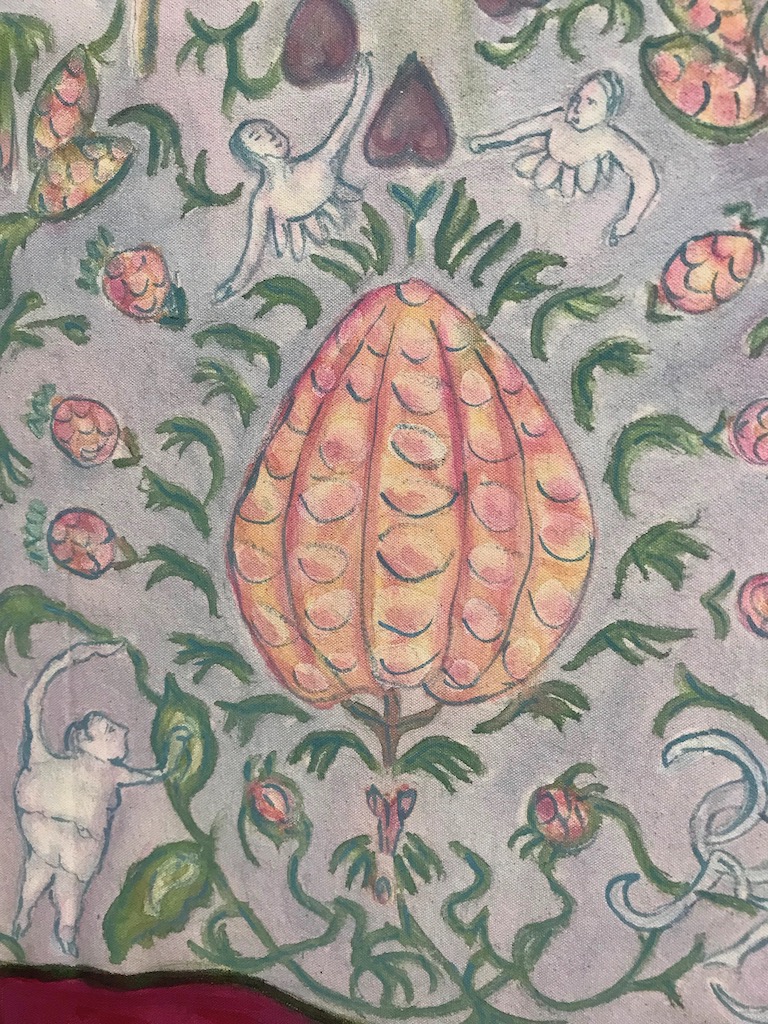

Paintings aim to re-create familiar beauty, strangeness, and ambiguity with significant stories residing in pattern. Full of tiny figures that tell stories of inequality, poverty and caring roles, there are also stories of transformation; metamorphosing hybrids, troll-like rock dwellers, fae-like flower-dwellers. Their stories can be pieced together like the land and they ask that we look below the surface to where they might reflect back to us purpose and belonging.Underpinned by nature, land is a physical pattern, an invisible web that creates a filigree of rich understanding between people, and similarly the domesticated patterns of the lives of women are full of myths about the value of care. Both nature and women have historically been oppressed and devalued, paintings aim to visually weaving new stories into culture about the value of the role of care, and life-giving.

The main hybrid figure gestures generously and exultantly above patterns of pomegranate that traditionally symbolises women and their power over life and death. Pattern is used to renew old symbolism, re-tell old stories and create new juxtapositions that counter-act the invisibility of women, mothers and carers. Hybrids and monsters are beautiful and disturbing; pleasing and grotesque. Metamorphosing figures occupy a gap or an interval ‘between what has been and becoming [something other]’.

About A common treasury for all

In 1649 a group of between twenty and thirty poor men and women began to dig the earth on St George’s Hill in Surrey. According to a government spy, ‘They invite all to come in and help them, and promise them meat, drink and clothes. . . . They give out, they will be four or five thousand within ten days. . . . It is feared they have some design in hand’.

Winstanley inspired the Diggers, a remarkable movement for land sharing and land rights, especially for its time. ‘A common treasury for all’ was part of his universal message of equality; access which envisioned an ecological interrelationship between humans and nature, acknowledging the inherent connections between people and their surroundings.

Perhaps even more remarkable for its time was that they allowed women some rights too. Whilst women have been historically symbolically represented as closer to nature because of their bodily function of reproduction (and also as something to be tamed and controlled) women have had few rights over the natural spaces around them. Women’s relationship with the land is complicated but then women lead complicated lives especially if they have family and domestic responsibilities. Home and hearth were their usual sphere of influence. Land girls during the Second World War were a rare exception in a history of absence in land working and land owning, but the war was soon over women were told to go back home to the kitchen sink.

In Britain where only 5% of the population own the majority of land and there is no ‘right to roam’ access to land the countryside is still very much contested and ‘rights of way’ become a great metaphor for the equality and freedom of women. Weaving these ideas with ecological and societal care, recent work explores redefining women’s relationships with landscape, nature and place, and giving them a central role.

Surreal ‘out of place’ juxtapositions between domestic and landscape explore domestic work and care; performing the body and interior stories ‘outside’, beyond domestic enclosures is subversive. Confronting, destabilising and transfiguring stereotypical stories and associations between women, nature and domesticity transcends domestic ‘bounds,’ and creates multi-layered fluid terrains of typically invisible Subjects.

A common treasury for all is a painting aiming to create an aesthetic of interconnectedness, social responsibility and ecological attunement.

Barbara Bolt writes of ‘painting as an event, a ‘summoning forth’. I wanted to create a ‘dynamic, entangled in counterpoint movement’ and ‘move in and out [of]… pictorial possibilities’, to create a chaotic yet connected profusion of figures. Using a limited palette of colours, figures and patterns are criss-crossed with green lines that are constellations and conjunctions between; the main figures lead an army of patterns in which figures invade and act. Even their clothing contain ‘interwoven information fields; with further figures. In total there are 48 figures in the patterns and landscape, and 34 more in the clothing.

This cast of approximately 100 figures, they all forge a ‘relationality-between’; proposing a dynamic view of women and a principled equality of Subjects in space. Snakes are utilised as a symbol of change and transformation. They are no longer a biblical indictment of women (through the temptation of Eve by a snake), snakes symbolise women’s potential for change and metamorphosis.

Moving through time and space, women can be free to choose how to represent themselves. Representing the value of care and compassion is the root of a vision of the world where women are gatekeepers, not only for the birth and care of future generations, but for caring for what really matters to the future of human kind. It is almost unimaginable to dream of how the world might change if this philosophy was adopted by all ‘mankind’.

Delpha Hudson, January 2024

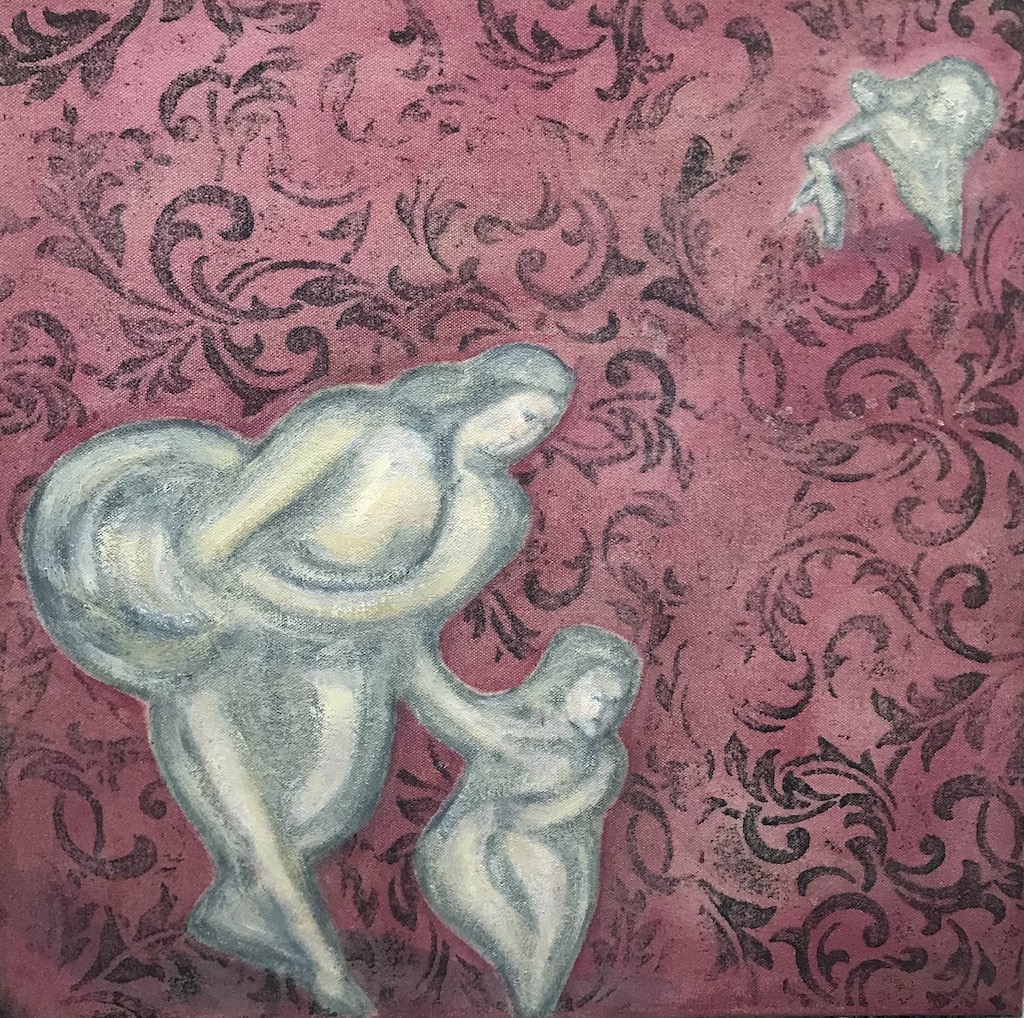

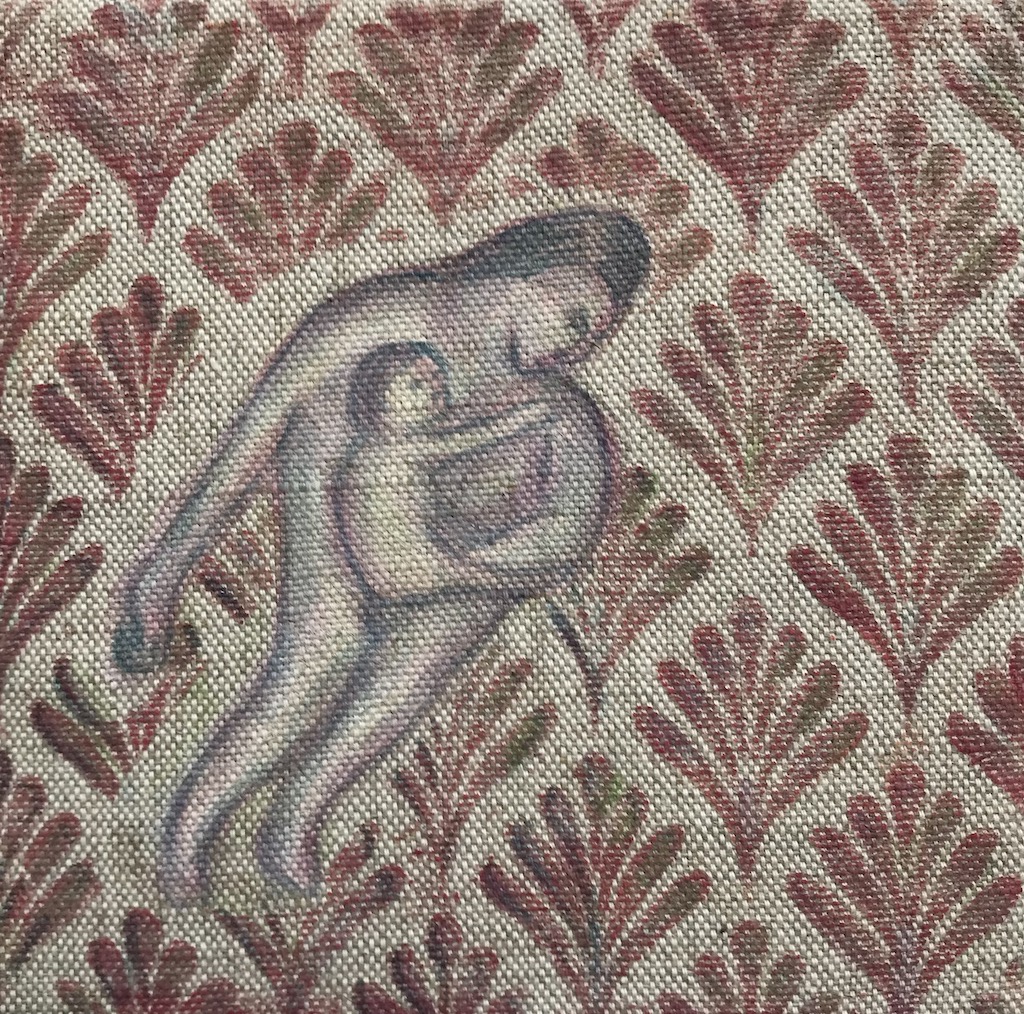

Smaller paintings that explore ideas surrounding narrative reframing, and cultural discourses about inherited patterns of socio-cultural expectations of women.

They started from the premise of the ‘carrier back theory of history’, most famously expounded on by Ursula K. Le Guin, that it was the ancient invention of the bag for gathering that was the true beginning of civilization. Usually one thinks of axes and tools for killing but thinking about a simple gathering tool and the women who gathered evokes a peaceful evolution – perhaps one that might inspire us now.

This narrative also links to my interest in representing the often invisible burden of parenting. These visual imaginings feel almost like portraits of missing people. Making and collecting stories that engender empathy, cultivate attitudes of care and that aim to create movement and to mobilise the body as more than a site of reproduction, or carrier of burdens.

Sneak a peek at one of the new paintings that will be on show at Penwith Gallery from January 31st 2025 in Telling Tales a joint show with ceramicist Debbie Prosser.

Do get in touch if you would like more information about paintings or connect to Delpha on Instagram @delphahudson