About this painting:

The title is taken from a phrase in Susan Griffin’s book ‘Made from this earth’.Griffin’s writing is a stream of consciousness, a multi-vocal meditation, a struggle to find a language within nature and organic life that is not controlled by patriarchy. The painting is an imaginative psycho-geographical meandering from Cornish granite walls, its old churches with their carvings, mythologies and misericords, to tales from ancient Greece. Connecting histories and places that are sites of conflict and resolution between nature and man.

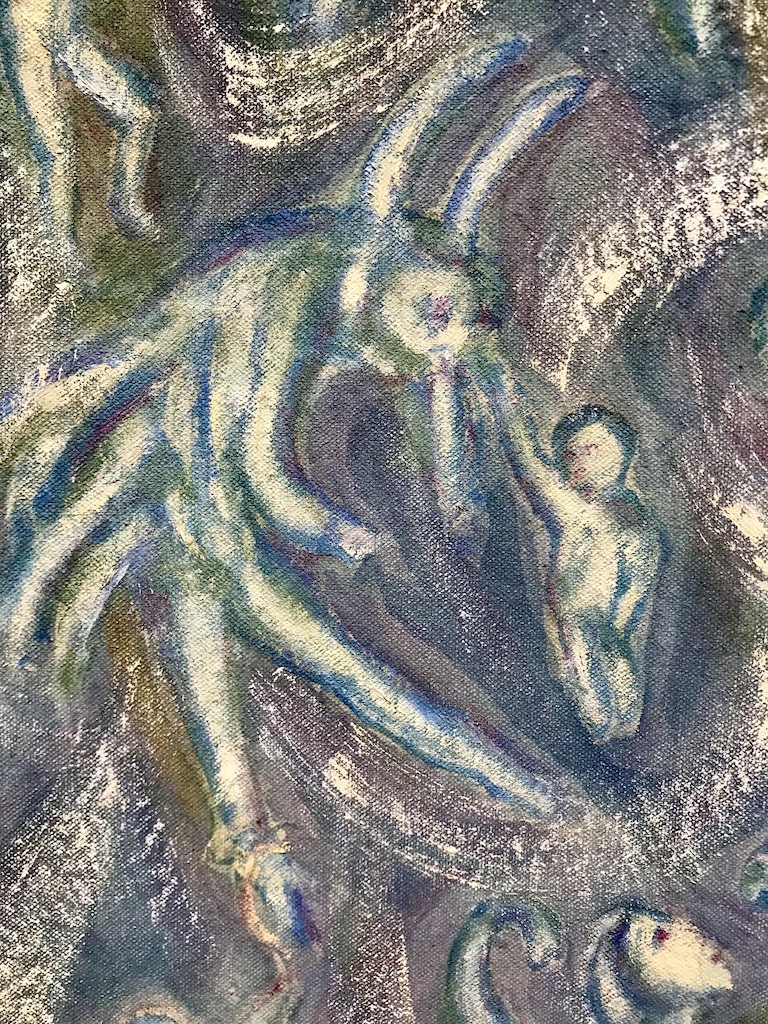

The mythical and implausible fabulation of a worm-like creature whose sinous irrepressible energy celebrates the female, the monster ‘goddess’ who for a substantial period of human history was respected before being co-opted by men. In ancient societies women had primary roles and goddess worship reflected this, Athena the goddess of wisdom originally honoured essential caring and domestic roles including weaving but over time she was named the goddess of war, ousted and appropriated with a shift to male military power in which women along with children animals and land resources became the prizes in raid and conquest. Greek mythology, like so many societal structures revel in the glorification of war. Understanding and re-imaging with these myths shifts us back to a different mode, way of understanding patriarchal power and control and perhaps mitigating what has become culturally acceptable.

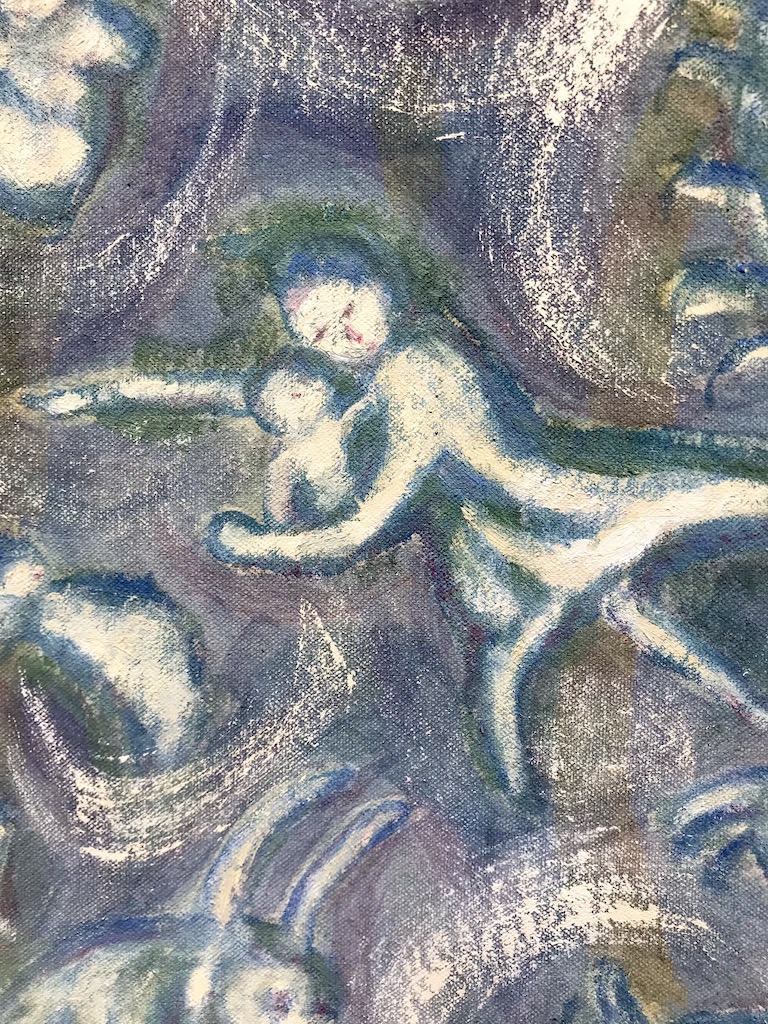

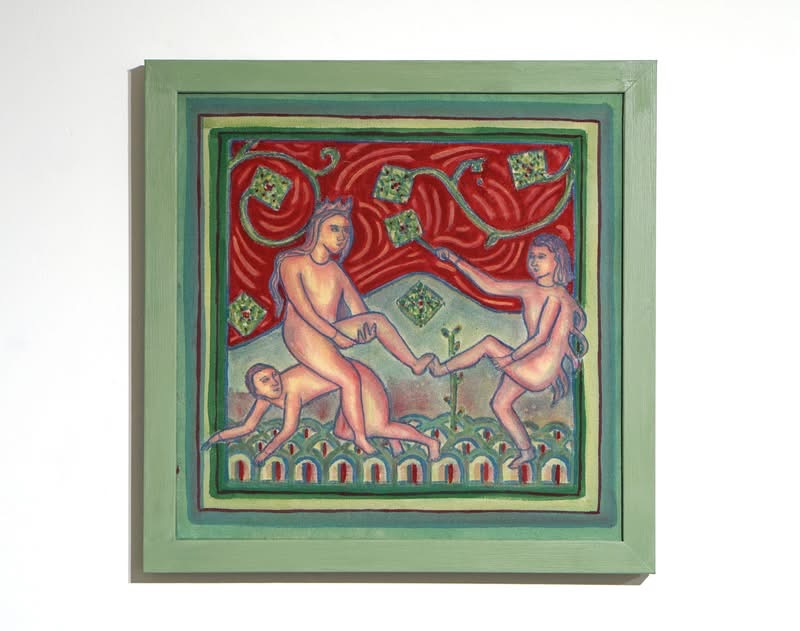

Mythologically an ambiguous ‘she’, ‘a bane to many men’ (as described by Homer in the Illiad) there is a fascination with the female body and the monstrous Other. In this painting she wears a fantastical yellow skirt or ‘poplos’. Every fourth year in August the Greeks celebrated the goddess Athena with a Panathenaeaic festival in competition with the more famous Olympic games. Amidst music, rites and epic poems a new embroidered robe was presented to Athena. A symbol of the fabric of society, it was raised to the wind to sail forth, in a resolution of discord into harmony. The golden ripeness of her skirt contains figures that replace triumphant battle scenes with celebratory images of women’s lives. Many are references to peaceful scenes from the Parthenon frieze (acropolis Athens c460), including a figure of a pensive Athena posed similarly to the famous sculpture of the male ‘thinker’. The stories contained within the skirt, speak of a different knowledge, a different grace from the qualities admired in a male-centred world.

Connecting goddess symbology to other ancient local traditions in Cornwall that feature a corn goddess and the infamous figgy dowdy goddess (from dowes) goddess of deep water, the sky is full of cryptids, mythical beasts and choughs, the Cornish bird symbolic of resurrection and conservation, they are also unpredictable fluid inchoate forms above some curious figures behind a Cornish granite wall. The role of these colourful and bizarre figures in relation to the central figure is intended to invite multiple readings and questions. It is not clear if they are hunting or harassing or celebrating. There is no correct answer and although this writing outlines some details about sources and referents, painting is not necessarily a prescriptive endeavour it invites imagination and multiple readings.

The border is loosely based on drawings from ancient Cornish churches with the appropriate link to misericords in which Misericorda from the latin means pity or mercy, these carvings often fold up to form a ledge to make comfortable standing during long services of worship, it has been noted that they often look like woman’s reproductive organs.

Merging multiple stories and fantasy, voicing deeply felt contradictions about place and women, the painting is a ‘binding song’ that craves connection between contemporary and historical myths and aims to undermine reductive and didactic narratives about women and their relationship with nature, place and society. Playing with tropes and re-imagining and re-imaging new ones, the ‘many faceted drama of creation and renewal, remembering and forgetting, interaction and transference of cultural exchange’ is a call for continuous change and continued struggle. The furies are still calling patriarchy out.

Delpha Hudson, March 2025

About this painting:

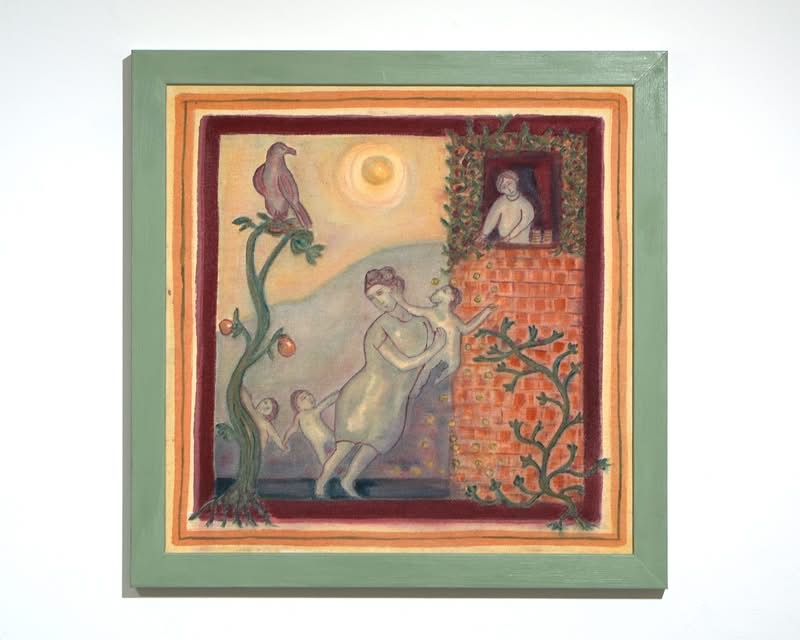

Painted to explore the maternal body juxtaposed with contrived human landscapes hinting at the patriarchal control of reproduction, nature, the land and representations of the ‘natural mother’. The ‘lie of the land’ is both how the landscape of motherhood in relation to landscape might look and explores lies about women and mothers.

Look carefully and medieval tapestry-like figures and motifs are woven together within intersecting planes that explore the lie about equality. Women are still doing the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work, or low paid jobs. Patterns create a palimpsest of time showing women working, caring, supporting; a rural ‘toile de jouy’ filled with humorous pastoral figures and scenes of women and children, farm animals, and even a donkey; an ancient Coptic pattern with weird hybrid creatures and women and children; a 70s pattern with womb-like shapes that contain not babies but women; borders of brightly coloured modern grotesques. Trees grow right through the painting. The main figure with a rucksack on her back is bent double holding a tiny baby very carefully in a tender gesture of care.

Just as ‘Cornwall was made by nature, then remade by miners’ representation of the mother’s body have been ‘remade’. Just as ecofeminism finds that women’s body as ‘closer to nature’ echoes the control of nature and landscapes by power structures created by men, this painting also references the lie about ‘wild Cornwall’. Appropriated and sold the ‘wildness’ of the Cornish landscape is promoted, commercialised and controlled, and the gentrification and monetisation of place does not benefit the majority of people who live there, many of them live in poverty and have to accept badly paid jobs to survive, never being able to afford to explore the landscapes they live in.

The mining or tourist elements of the painting did not appear during the painting process. The tiny baby was a late addition too and became an additional metaphor for care and responsibility. Perhaps also personal as I still often have recurring dreams of small babies that are not my own but for whom I am somehow responsible. Left in my care, these are disturbing, anxious dreams. I must make sure they are cared for.

Delpha Hudson, January 2025

There are always new watercolours and paintings waiting to be added to this page. In the meantime look at Delpha’s instagram and follow for new work in progress or get in touch.