Shown at UNDER/OVER AT G12 GALLERY REDRUTH, 2023

Inspired by the theme of the show and thinking about cyclical renewal, magic carpets and transformation – as well as many other themes – this grotesque style octagonal floor painting was created especially for the site and the theme Under/Over. Read more about this art work.

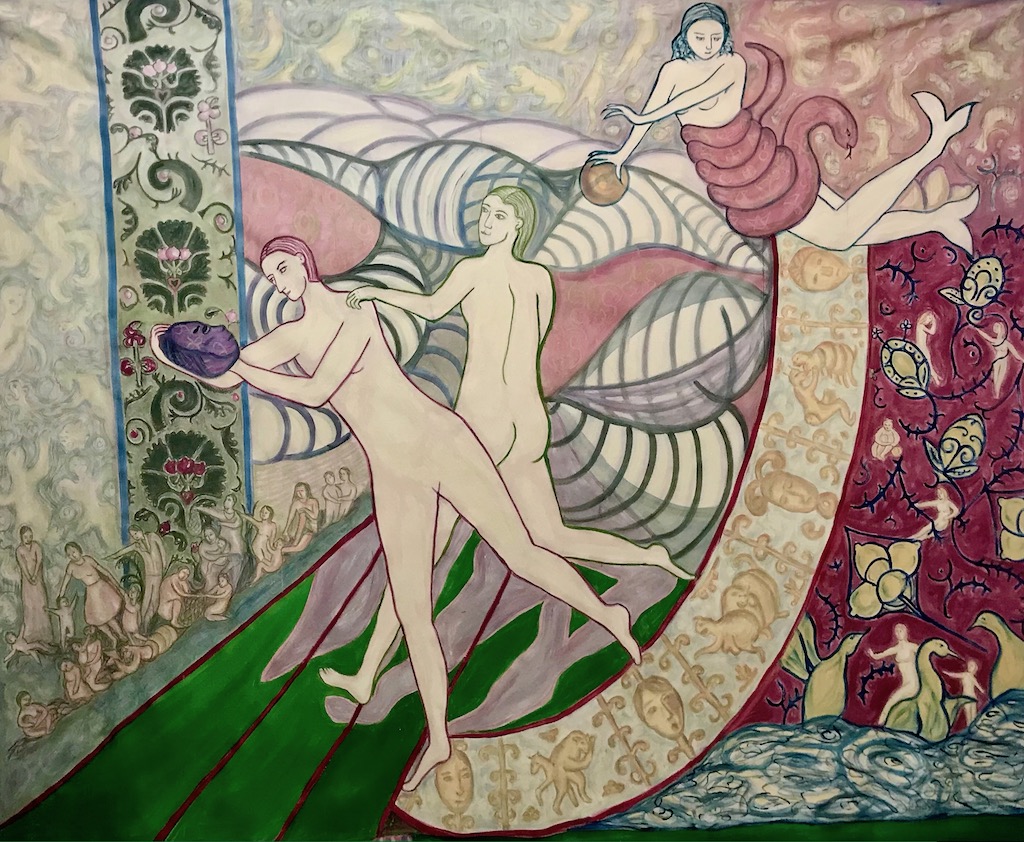

Shown at Tremenheere Gallery, 2023 Read more about this art work..

As infinitely boundless as the human heart, acrylic on canvas hanging, 210x160cm

As I added finishing touches to this painting…..besides symbolic imagery of landscape and women, I know subconsciously I was thinking about war and…peace.

Both ukarinae and Russia, like all eastern European countries have a tradition of Berehynia…she is the Goddess of protection, land, and nature. With her symbolism of 2 birds (doves) she is a symbol of peace. … as a wood spirit, loving the land, protecting it and the people that care for it.

Undoubtedly both sides of the war in Ukraine invoke her protection of their land and spirit, perhaps sadly in a nationalistic sense. Yet she if she could be a universal symbol above political and commercial interest, she would be a symbol of peace: protecting all that live and care for the land against political agenda, aggression, and commodification of assets.

Of course, I fully support Ukraine as an evil necessity. I wish there was a way to see an end to the horror of war. This painting is a reminder of the deluge of war, the suffering (primarily of women and children); and visualising an idealism about our relationship with the places we live; that ecology is often thinking about a larger picture of human politics and greed; what a different world could exist if we could unite and care for the land around us by overthrowing destruction, and tyranny.

There’s lots more writing about on @delphahudson

Notes on Creatures that tip the scales in our favour, 2023

I wanted to make this painting move through landscape and evoke our relationship to nature -and each-other; to look through opaque and permeable figures, pareidolic skies, grotesques and shadows, and think about how we got here (the present) and enable us to imagine different possible futures.

Painting produces decorative and imaginative reverberations, extraordinary spaces to register presence and connectivity. Art enables is to forge connection and reinvent value (from Guattari ‘3 ecologies’ writing about ‘ecosophical praxis’). Lubaina Himid talks of painting as a place of encounter, and the three figures in this painting intentionally have an inter-locking, inter-twined connectedness; they are a trinity, a ‘plaiting’ that creates a network of movement.

The figures are idealised forms imbuing the painting with other-worldly allegorical resistance of myth and timelessness. They are avatars or personas that have universal application of embodiment and identity. They speak of our potential for connected to others, and to our capacity to be permeated by other selves and other people without being fractured by them.

The painting is a visual mediation of space animated by material phenomena and patterns where figures create psycho-geography connecting subjects and places.

Using mythological and archaic sources in order to record the ambivalent relations between the sign, ‘woman’ and women as historical subjects within nature, there has always been a troublesome essentialism when dealing with women/nature. Fear of a persistent negative conflation of women with nature has so often divided women from a special relationship with nature/the world, yet as Stacy Alaimo states,

[it is] ‘important to take up and transform the discourses that hold sway, to rearticulate rather than run from whatever has cultural potency..[and] develop and promote alternative visions’ (Undomesticated Ground, p. 183)

The female body in language/nature has the potential to create new lexicons that unmask the power of the stereotype, and displace fixed categories and value hierarchies. They (the figures) are the inhabitants of a landscape that uses sly linear eruptions to create a Venn diagram of connectedness – to themselves, each other, to others – and to landscape/nature. Their movement implies some story is unfolding, it unsettles our attention, leading the eye to patterns, symbols, and curved lines that extend into infinity.

Barbara Bolt writes of ‘painting as an event, a ‘summoning forth’,

‘we are caught up in dynamic, entangled in counterpoint movement…we move in and out and caught up in the pictorial possibilities and in this way the ‘bloc of sensation’ plays out’.

(‘Unimaginable happenings’ essay in Deleuze and Art)

The gestural female body becomes sensation, a vehicle for fluid connectivity and metaphor for the physical and psychic experience of empathy and care. Painting is a performance and event and ‘it is through the interconnection of events, occurring at different speed that an assemble is constructed …..producing different connections and syntheses’. (Deleuze and Guattari: 1994:173-4)

The possibility of multiplicity and re-singularisation of the body created in painting events explores women’s societal caring roles and aims to reinvent value. Forging relationality-between; proposing principled equality and a dynamic view of women who constantly move through time and space with the possibility of change and metamorphosis. We all have a

‘vivid longing for a created presence of the imaginary…as an illusion of the impossible,’ (from Marina Warner’s near eponymous writing about chimerae and monsters [from monstare – to warn]) The impossible it seems is the necessity that we think ‘permeably’, that humans understand their survival is dependent on their connectedness to nature (the health of the planet) and to each-other; that the human condition is to be interconnected through empathetic and caring acts.

Delpha Hudson, June 2023

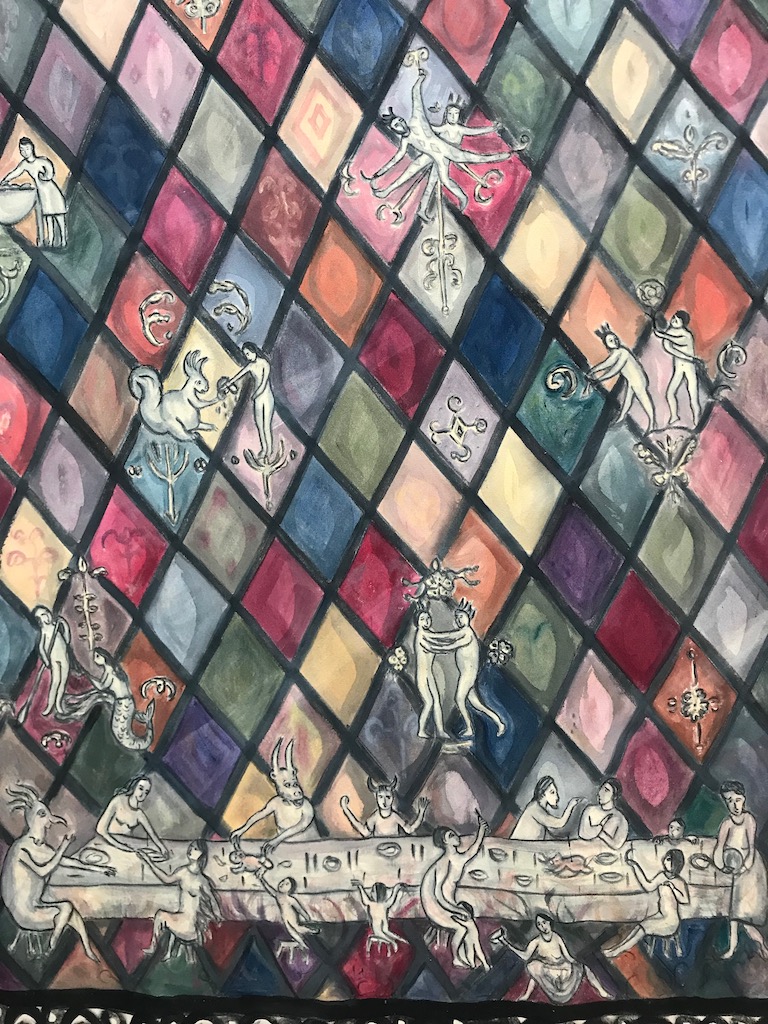

Notes and research on If women had written stories, 2023

This painting explores social and political threads encountered in traditional literary works about women, aiming to weave and renew narratives into our everyday relationships, and personal and private spaces. Painting becomes a kind of patchwork, a way of thinking through complex systems through multiple, intersecting and entangled voices.

If women had written stories celebrates gender equality. Inspired by Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, I wanted to explore what has changed and what has not over the last few hundred years. This paintingexplores contemporary societal value, judgement and visibility for women and representations of equality – or ‘sovreighty’ as Alisoun, the Wife of Bath names it in old English.

Who peyntede the leon, tel me who?

By God, if wommen hadde writen stories,

As clerkes han withinne hire oratories,

They wolde han writen of men moore wikkednesse

Than al the mark of Adam may redresse.

(ll. 692–96 Chaucer’s Wife of Bath’s Prologue) Or in the contemporary English:

Who painted the lion, tell me who?

By God, if women had written stories,

As clerks have within their studies,

They would have written of men more wickedness

Than all the male sex could set right.

I love the rhythm, the pungent vowel sounds and rhyming of the original, there is a delicious pattern to the words that are often mysterious. I love guessing the meaning and trying to understand the multitude of other literary references that Chaucer makes. Chaucer’s poem is divided between story telling, satirical analysis of human personality, and a commentary on theory, ideas, religion and philosophy. Chaucer writes in dialogue with religion and dogma. He creates his character Alisoun, the Wife of Bath, who converses with not only her fellow pilgrims but historical and religious writers – and I like to think to us, 700 years later. She forthrightly denounces patriarchal writers, knowledgeably quoting them and satirising contradictory doctrines (eg after all how can scripture say women must be virtuous virgins and hope for a continuation of the human race?! )

There are many voices in Chaucer’s text and Bakhtin’s notion of dialogism; of interweaving/interleaving texts (whether written or visual) comes to mind. Painting with reference to existing multiplicities of voice, add yet more versioning and voices. I do sometimes think of painting as a dialogic process; being-in-conversation with myths, stories, ideas, places and visual symbolism…(to name a few) .. Weaving together inspirations and ideas, references go backwards and forwards in time to create multiple conversations Chaucer’s ideas and sources, personal experiences and contemporary culture.

So threaded within the painting are multivalent references that garner a relationship with all the things I love about language and this poem; Alisoun speaks out passionately, knowledgeably intelligently and with ‘experiaunce’, I like to think through visual means and a language of painting I renew and rewrite her message.

About lions

If lions painted pictures of lions the story would be different. Aesop’s fable points towards the bias with which man depicts his own version of the truth. Geoffrey Chaucer draws inspiration from this fable in this tale in which Alisoun compels her audience into listening, and whilst she acutely questions the then existing dogmas of social hierarchy, inequality and religious and patriarchal restrictions for women using her wit, honesty, personal experience and learnedness. I draw from this the challenge; that if women painted lions they would look different.

The image of a painted lion reminds us that the object of much male discussion and religious doctrine is the behaviour of women, yet women, like painted lions, are in medieval times unable to create their own portraits, either of themselves or of men. Chaucer, through Alisoun, draws attention to this central inequality in medieval society and male control over both ‘writen stories’ and ‘oratories’. I reflect with surprise about what has changed since 1387 and what hasn’t. Many women still do not have power over their stories and how they are represented.

About Alisoun

She is a memorable, remarkable and powerful character, she is ‘the riotous, …authentic Wife of Bath means something to everyone. She’s still the spiciest 600-year-old in town’. (1)

She is outspoken, philosophical, literate, and funny. She is well suited to speak her experience and refuses to be frightened into submission with an astonishing display of learning is half comic device, half impressive dismissal of the usual tropes about historical women (or contemporary women for that matter). She is honest about her flaws, unlike other characters in other in medieval fiction that are typically grotesquely comic hypocrites. She is full of contradictions, but we can’t help but like her, feel empathy for her and laugh with her – not at her. Alisoun’s prologue is “a staggering 856 lines long.” (2)

it is the longest poem and she is an obvious favourite appearing in other places in Chaucer’s writing. Her most amusing darts are not necessarily her most important, for her primary attack in both the prologue and the tale is directed at a body of marital lore held commonly by her own class and articulated most fully in the deportment (how to behave) books written to foster “gentilesse”. Lets interpret the notion of “gentilesse” as one way powerful societal expectations, and the construction of women’s behaviour were used to control women. In the deportment books that Alisoun so effectively trashes, (through expert argument) the husband is a father-god, all-knowing, and all-powerful; the wife is charged only with keeping his honour and estate by practicing absolute obedience. This exemplifies a biased lion painting at its worst. Indeed the women are either invisible, or owned like chattel. (3)

Similarly, though Alisoun might be mocked for her independent-minded boldness, almost monstrous by medieval ideals of femininity, those very ideals are, as Chaucer has her point out, the work of men. By referencing Aesop and the lion painting, Alisoun reveals her own fine comic understanding both of the delights of lion painting, and its essential untruthfulness.(4) Her story about her victory as a wife over her lord and master, (as husbands were seen in the eyes of society), is a subversion of the medieval order, farcical as she a temporarily and amusingly up-ends social norms. Alisoun challenges ‘maistrie’ and in her tale (the fabliau of the Loathly Lady (5) expounds the idea of a balanced partnership between men and women, husbands and wives, one in which she talks of ‘sovreigntee’ (equality in contemporary English).

Alisoun’s prologue is about truth and experience; her physical experience and her excitement of scholarship and ideas; reason in collaboration with a life of feeling. It is lived experience without legitimising the power of the personal over knowledge and theory. Just as the two are held in perfect balance, so are the competing claims of men and women. Alisoun is honest about her behaviour arguing that ‘a woman has no other means to ‘redresse’ the balance of power’. The empathy we feel for her and her ‘divided temperament’ is real. She is full of contradictions, we like her and laugh with her about her successes and tribulations.

If women had written stories is an imaginative synthesis, a product of fusion between ideas and lived experience that aims to reconcile duality, and create connections and conversations with the past though visual means. Painting is a marriage of learning and experience. It organises material that, in this case, refers to antiquated compositional structures (like books, manuscripts, old windows…) and ‘quotes’ in similar ways to the spoken word. There is a constant re-involvement and re-creation of dialogue through painting that creates socially charged conversations between now and the past. Small figures make carnivalesque references, in many voices (some that refer to May Day celebrations (6), creating relationships between amusing folk, and high culture. For Bakhtin, the carnival was an equalizing force, that allowed high and low culture to mix (7).I think figurative and figural contemporary has the same potential to explore levelling humanity.

Painting an obscure past, it is never so distant that it is not resonant of now & can’t be rewritten and reimagined.The dark shading works like a veil, a pall on the bright colours used in the fenestral diamond pattern, yet there is fun, frolics and a playful unmasking. This painting endeavours to play with multiple voices that exist in this text/in all texts, and it questions who is writing (a man), who is speaking (Alisoun); contemporary societal value, judgement and visibility for women is a joint enterprise for everyone.

Alisoun’s use of the fabliau of the Loathly Lady is salacious reading resolved into a happy ending and the question that this tale purportedly answers is the question: What do women want? Alisoun/Chaucer disclose a striking unvarnished truth that what women want is ‘souvreigntee’ – equality. Hundreds of years later, it is what they still want.

References and footnotes

1. Katy Guest in the Guardian on : The Wife of Bath: A Biography by Marion Turner).

2. ” ” “‘The tale she tells, and the other pilgrims’ reactions to it, would also be familiar. Turner mentions “no other pilgrim is interrupted as much”. She is also mocked for her witty outspokenness and her unashamed sexuality. The assumption that female pilgrims were a licentious lot is made plain in a magnificent image of a 14th-century pilgrim badge. It shows a vulva on legs, wearing a pilgrim’s hat and carrying a set of rosary beads and a phallus on a stick.’

I enjoyed scattering references to pilgrims in the painting as it relates to an early ‘tourism’, … a common experience to all that live here in Cornwall; wearing your pilgrim’s badge on your hat is like any souvenir: a visual reminder for everyone else (as you can’t see it yourself) perhaps of your spiritual journey, but also a proof of having been there.

There are also symbols in the painting like crosses and scallop shells. There are many stories of the scallop shell. One story recounts that after James was martyred in Jerusalem in the year 44, his body was taken to Spain and when the ship reached the shore a horse was spooked and fell in the water. The story goes on to say how both the horse and rider were miraculously saved and came forth from the water covered in scallop shells.

3. Chattel – Women were often owned like cattle and other household items with no power of their own yet Chaucer’s character Alisoun indicates there were exceptions for enterprising women, many who did business and owned estates and business after the Black Death. Sadly these rights were regularly eroded by new laws and social mores.

4. CARRUTHERS on Chaucer’s Wife of Bath

5. The couple in bed in the top left hand corner is a mocking reference to the frontispiece of an illustration by Edward Burne-Jones. It does not portray the knight and the ‘loathly lady’ but portrays a couple rather enjoying themselves.

6. Carnival references include masquerade characters inspired by a 16th Century V&A window (with the diamond panes of course) with characters like the maid and the captain dancing posing and gesturing in celebration of May 1st or ‘mery may’. The figures are archetypes similar to the commedia del’arte and communities would dress to mix up societal hierarchies. Disguise was a key part of such ‘guises’ and celebrations. Later centuries saw Harlequin (and harlinquinade) become the key figure dressed in diamond-patterned outfits of course.

7. The left hand bottom section features a meal table with all-comers, children creatures, different characters and social classes all sitting and eating together.

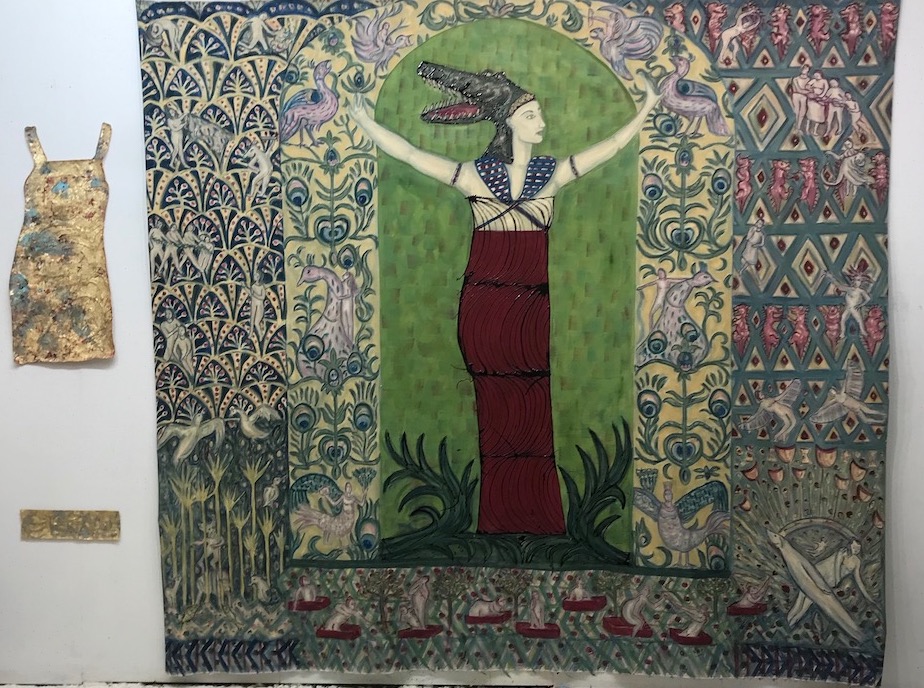

Notes on When you’ve been around so long you are goddess of many things installation with golden apron. Installation at Tremenheere Gallery, 2023

This painting can be interactive and installed with the invitation to add the golden apron to the main figure as an expression and award of value.

The largely unknown now, yet in her time significant Egyptian Goddess Neith was worshipped by the Egyptians for over 2 thousand years. From early in the Pre-dynastic era through to the arrival of Roman rule, she had been: the goddess of creation and the first and the prime creator. Then she was the Goddess of wisdom, water, rivers, mothers, childbirth, hunting, weaving, and war. Yet who has heard of her now? I hadn’t.

Humorously sardonic, the title reflects with irony on how contemporary society grows tired of things that have been around for minutes, let alone a long time. This multi-layered painting celebrates and questions the value with assign to women’s lives and invites you to actively engage with its socio-political themes. History and contemporary society resigns women to less celebrated roles than ‘goddess’ (‘kitchen goddess’ does not have the same ring) – or has simply written them out and forgotten them. Despite Feminist goddess art of the 70s and its recent revival, it seems impossible to imagine that women were worshipped anciently. Post-Egyptian Judea-christian religions (that have only just been around for two thousand years) created patriarchal systems that have shaped deep-seated prejudices about women. Respect is so often merely lip-service, as women remain ‘goddesses of many things’ (usually smaller, less valued things like multiple badly paid jobs, home, housework, children, care of elderly relatives).

When you’ve been around so long you are goddess of many things is a colourful patchwork that links complex systems of representation and thought. The hectic patterns are redolent of Egyptian symbolism and Medieval art create an opulent eclectic mix that mocks ancient hierarchies that contain and misrepresent women. The painting is filled with tiny details that ooze from structures and patterns. Small chimerae and figures weave in and out, telling a multiplicity of stories. The medieval style Nile delta at the bottom of the painting was inspired by Salisbury Cathedral ‘doom’ paintings, with the dead rising from small red boxes (graves I presume), and they enact a kind of Spencerian Resurrection, which is appropriate to Neith, a funerary goddess. Death and afterlife were much bigger questions for ancient societies it seems, and their thinking about how to ‘live for ever’ dependent on spells to fool the gatekeeper Horus (found in the ‘Book of the dead’), yet despite our societal differences, themes of money, power and prestige is a common thread between ancient and contemporary society. The rich still ensure they are celebrated and remembered (by creating huge monuments and leaving their treasures) to the denigration of poorer working people – whom, as statistics show are so often disadvantaged women.

Whilst painting I think about the way I paint stories, and wonder: is it a kind of vernacular? As an adjective vernacular can mean ‘spoken as one’s mother tongue; not learned or imposed as a second language.’ The language is not entirely my own, I speak in tongues, using diverse visual references that invoke ancient modes of thought and expression. Figures and stories are woven into them to expose multiple viewpoints, subjectivities. Neith’s story is one continuity and change. There are peacock and dragon references in Morris style patterns, circling around Egyptian influences on the Arts and Crafts movement. The peacock symbolises beauty, rebirth, eternal life – as well as many other diverse interpretations – a great example of how symbols change and morph as meaning is never static. Symbols of metamorphosis and fluidity are significant in story telling in which the ending can always be different because we have the ability to change them. Visually reinvigorating myths in painting is about visibility of women and an exploration of care, value and economic status. The grander overall picture of humanity is about creating and assigning value through stories.

Aprons signify many things. Historically they could be insignia, badge of honour, a symbol of power (the masons use aprons with fig leaves), yet they are better known as a uniform for workers. Aprons symbolise work, domesticity, and utilitarian tasks where clothing needs to be protected from messy substances (food, blood, ….). The golden apron, provided so that it can be added to the figure in the painting, is like a trophy or award, yet it is also textured and tarnished. This is an item used to symbolise hard work and graft, and a reminder differing kinds of value.

So let’s play around with stories and aprons to re-invent value and forge new relations between symbolic spaces and the human condition. Let’s create diverse contemporary-historical narratives through a patchwork of complex systems of thought, including Carnivalesque humour that characterises freedom and equality. Powerful and differentiated images of women help us to fight daily to retain rights (physical, mental and economic) that are so quickly eroded, undervalued, and made invisible by the bedrock of patriarchy and prejudice. So we’ll keep laughing (and occasionally crying) as we keep asking for more.

Delpha Hudson, 2023

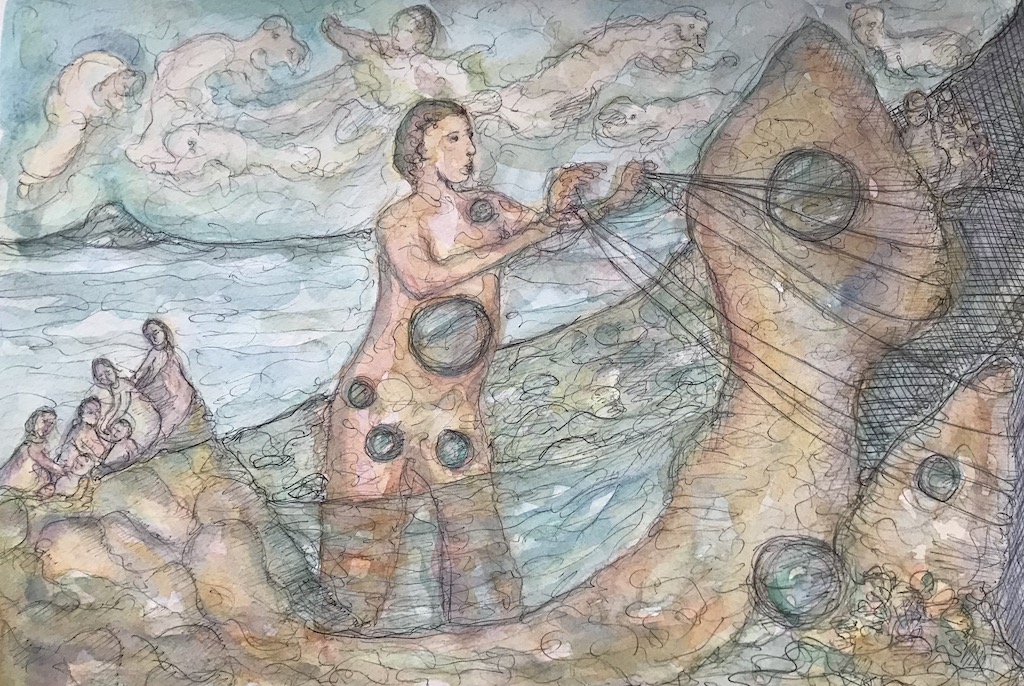

Some notes on the use of opaque and translucent figures & porosity

The most opaque colour is white, it does not absorb light giving the impression of purity and luminosity. We cannot see light, we rely on the impression of absence and of depth and shadows. Like a mirror white cannot be seen through.

I use the opaque lightness of figures to explore visibility and absence, yet also try to balance it with translucency. The figures are white with the merest hint of depth and shadow. They are both ‘opaque’ and ‘translucent’; both full of light and yet porous. Porosity interests me as women its seems are often more permeable than men. Porosity and permeability have been used to describe the ability of humans to think of others, to have fewer boundaries and greater empathy. I love the seeming contradiction of working with opacity and translucency; impermeability and porosity.

As a way of evoking connectedness, these female figures are visible and meld into their landscapes in many ways communicating the loss of self through others. Something the human race depends on yet is often given by women at huge personal loss.

Seeing through and being seen was inspired by porous rocks of the Algarve coast, Portugal. Delpha will be on a residency in Portugal, November 2024.

Read more about paintings as they are created on instagram @delphahudson